UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, DAVIS

INSTITUTE OF TRANSPORTATION STUDIES (ITS)

Executive Summary

Ride-hailing services have experienced significant growth in adoption since the introduction of Uber, in 2009. Although business models to support the sharing of vehicles (e.g., carsharing) have been present in the United States for more than 15 years, their adoption has been somewhat limited to niche markets in dense, urban cities or college campuses. To date, carsharing has attracted over 2 million members in North America and close to 5 million globally. Conversely, this new model of “shared mobility” is estimated to have grown to more than 250 million users within its first five years.

The rapid adoption of ride-hailing poses significant challenges for transportation researchers, policymakers, and planners, as there is limited information and data about how these services affect transportation decisions and travel patterns. Given the long-range business, policy, and planning decisions that are required to support transportation infrastructure (including public transit, roads, bike lanes, and sidewalks), there is an urgent need to collect data on the adoption of these new services, and in particular their potential impacts on travel choices.

This paper presents findings from a comprehensive travel and residential survey deployed in seven major U.S. cities, in two phases from 2014 to 2016, with a targeted, representative sample of their urban and suburban populations. The purpose of this report is to provide early insight on the adoption of, use, and travel behavior impacts of ride-hailing. The report is structured around three primary topics, key findings of which are highlighted below.

Adoption of Ride-Hailing

- In major cities, 21% of adults personally use ride-hailing services; an additional 9% use ride hailing with friends, but have not installed the app themselves.

- Nearly a quarter (24%) of ride-hailing adopters in metropolitan areas use ride-hailing on a weekly or daily basis.

- Parking represents the top reason that urban ride-hailing users substitute a ride-hailing service in place of driving themselves (37%).

- Avoiding driving when drinking is another top reason that those who own vehicles opt to use ride-hailing versus drive themselves (33%).

- Only 4% of those aged 65 and older have used ride-hailing services, as compared with 36% of those 18 to 29.

- College-educated, affluent Americans have adopted ride-hailing services at double the rate of less educated, lower income populations.

- 29% of those who live in more urban neighborhoods of cities have adopted ride-hailing and use them more regularly, while only 7% of suburban Americans in major cities use them to travel in and around their home region.

- Among adopters of prior carsharing services, 65% have also used ride-hailing. More than half of them have dropped their membership, and 23% cite their use of ride-hailing services as the top reason they have dropped carsharing.

Vehicle Ownership and Driving

- Ride-hailing users who also use transit have higher personal vehicle ownership rates than those who only use transit: 52% versus 46%.

- A larger portion of “transit only” travelers have no household vehicle (41%) as compared with “transit and ride-hail” travelers (30%).

- At the household level, ride-hailing users have slightly more vehicles than those who only use transit: 1.07 cars per household versus 1.02.

- Among non-transit users, there are no differences in vehicle ownership rates between ride-hailing users and traditionally car-centric households.

- The majority of ride-hailing users (91%) have not made any changes with regards to whether or not they own a vehicle.

- Those who have reduced the number of cars they own and the average number of miles they drive personally have substituted those trips with increased ride-hailing use. Net vehicle miles traveled (VMT) changes are unknown.

Ride-hailing and Public Transit Use

- After using ride-hailing, the average net change in transit use is a 6% reduction among Americans in major cities.

- As compared with previous studies that have suggested shared mobility services complement transit services, we find that the substitutive versus complementary nature of ride-hailing varies greatly based on the type of transit service in question.

- Ride-hailing attracts Americans away from bus services (a 6% reduction) and light rail services (a 3% reduction).

- Ride-hailing serves as a complementary mode for commuter rail services (a 3% net increase in use).

- We find that 49% to 61% of ride-hailing trips would have not been made at all, or by walking, biking, or transit.

- Directionally, based on mode substitution and ride-hailing frequency of use data, we conclude that ride-hailing is currently likely to contribute to growth in vehicle miles traveled (VMT) in the major cities represented in this study.

1. Introduction

The emergence of shared mobility services, such as Uber, Lyft, and Zipcar, are disrupting established transportation business models. The notion of “shared mobility” is part of a broader concept often called the “sharing economy” through which information technology has enabled the shared use of assets and services, ranging from housing (Airbnb) to small jobs and tasks (TaskRabbit). In this report, we focus our discussion on the sharing of vehicles through carsharing (e.g., Zipcar, car2go) and ride-hailing (e.g., Uber, Lyft). Through the collection of a large, representative sample of survey respondents in seven major metropolitan areas, we explore the adoption, utilization, and early impacts on travel behavior of shared mobility services.

The rise of ride-hailing has sparked significant debate in cities around the world on a variety of issues including how they should be regulated, their safety implications, and how they influence travel behavior. Some suggest that shared services help reduce vehicle ownership and increase use of public transit, while other evidence suggests that they may lure riders away from transit and add to already congested streets. The existing research on how ride-hailing influences travel behavior is somewhat limited due in large part to the recent, rapid growth of these services, and the lack of publicly available data for transportation planners and researchers to assess how, when, and why these services are utilized.

Shared Mobility: A Changing Landscape

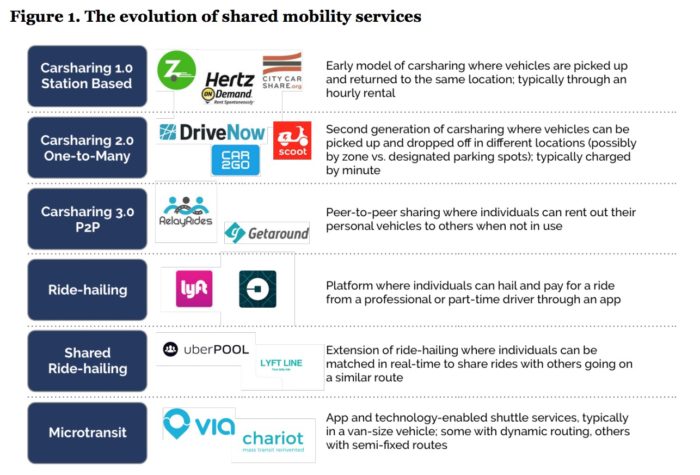

First, we begin with a brief overview of the evolution from traditional carsharing programs to ride-hailing services, and the distinct features of these business models. In prior transportation literature and in the public sphere, it has been common to bundle these services and their associated impacts together. However, for reasons explained throughout this report, we believe it is important to distinguish between the different models and their impacts. Figure 1 presents the evolution of shared mobility services over the past two decades.

Traditional carsharing models, such as Zipcar, emerged in commercial form in the late 1990s in the United States. Through carsharing, individuals or households typically joined a member-based program through which they gained as-needed access to a vehicle that they then drove themselves. Two strategic advantages of early carsharing programs included the following: 1) carsharing vehicles were typically located in accessible locations throughout a dense, urban region; and 2) members were able to borrow the vehicles on a short-term hourly basis.

Although traditional carsharing programs continue to be popular topics of transportation research and public discourse, total North American carsharing members in 2016 was estimated to be 2 million, less than 0.7% of the current U.S. population. Based on these figures, we suggest that traditional carsharing services continue to serve a fairly niche market. However, the initial disruption of carsharing programs has spurred the development of similar programs by rental car companies (Hertz 24/7) and major automakers (Daimler’s car2go in 2008, BMW’s ReachNow – formerly DriveNow in 2011). An interesting new feature of the latter carsharing models is the ability to pick up a car at one location and drop it off at another spot or service area (one-way or free-floating carsharing).

The widespread adoption of smartphones embedded with GPS, combined with the availability of digital road maps through APIs, provided the necessary enabling technologies for ride-hailing services. Uber was one of the first services to emerge in 2009, however several similar companies have also entered (and some departed) this new market in subsequent years (Sidecar, Hailo, Lyft, Didi Kaudi). The common feature of ride-hailing services is the ability for a traveler to request a driver and vehicle through a smartphone app whereby the traveler’s location is provided to the driver through GPS. With the support of GPS technology, digital maps, and routing algorithms, users are provided with real-time information about waiting times. Proponents of these services argue that they provide a more safe, reliable, efficient transportation experience. However, others argue that they essentially operate as illegal taxis. While the regulation of these services continues to evolve, there is agreement on one issue: ride-hailing services have begun to disrupt traditional transportation systems in cities across the globe.

When ride-hailing services were first launched, they were commonly referred to as “ridesharing” or “peer-to-peer mobility” services. Many experts initially argued that this label was a misnomer because drivers and passengers did not share the same destination, 5 but rather, the drivers provided services analogous to limousines or taxis. In 2013, a California Public Utilities Commission ruling officially defined these services as transportation network companies (TNCs), although they are still often colloquially referred to as ridesharing, and more recently, ride-hailing services.

In 2014, both Uber and Lyft announced the pilot of new products that harness algorithms to match passengers who request service along similar routes in real-time, enabling them to share rides (UberPool, LyftLine). Although the paid drivers of UberPool and LyftLine rides typically do not share the same destinations as their passengers, other business models and apps are emerging in an attempt to enable traditional carpooling – where the driver does indeed share a similar route (Waze’s Rider, Scoop).

Both carsharing services and ride-hailing services both reflect a shift away from vehicles as a product to vehicles as a mobility service. However, we find that the service models and rates of adoption are quite different, with ride-hailing services attracting a much larger and broader segment of the total population. The results of this study focus primarily on ride-hailing. In this report, we present new evidence on the adoption, utilization rates, and early impacts on travel behavior of these rapidly-growing services.

The remainder of this report is organized as follows. In Section 2, we elaborate on the academic and industry research on shared mobility adoption and their potential impacts. Section 3 briefly describes the methodology for the data collection. Section 4 presents early data on the demographics of ride-hailing adopters, utilization rates, and their correlation with earlier carsharing services. Section 5 examines vehicle ownership rates and potential impacts of ride-hailing on vehicle use. Section 6 presents data on the relationship between ride-hailing and transit use. We conclude with a discussion of this study’s key findings, potential policy implications, and directions for future research. The findings presented here represent one study of a series of evaluations on future urban mobility trends based on this dataset.

About the UC Davis Institute of Transportation Studies (ITS)

its.ucdavis.edu

The Institute of Transportation Studies at UC Davis (ITS-Davis) is the leading university center in the world on sustainable transportation. It is home to more than 60 affiliated faculty and researchers, 120 graduate students, and a budget of $12 million. While our principal focus is research, we also emphasize education and outreach.

Tags: carsharing, Impacts of Ride-Hailing, Institute of Transportation Studies, ITS, ride-hailing, UC Davis, University of California

RSS Feed

RSS Feed